Support Science Learning with Clay Animation

Make science concepts tangible with this fun and creative activity.

Clay animation is a motivating process you can use to engage students as they explore and grapple with complex scientific topics. Science education is designed to provide students with the skills to become independent inquirers about the natural world. The National Academy of Science encourages teachers to use collaboration as a tool so that students participate in the sharing of data and development of group reports. They also suggest that students should be given opportunities to make presentations of their work and “engage with their classmates in explaining, clarifying, and justifying what they have learned.” Clay animation is perfect for supporting this learning environment!

Make Science Processes Tangible

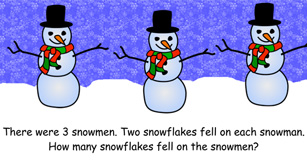

First of all, clay animation helps make many science processes and concepts tangible. In What Works in Classroom Instruction, Marzano explains that humans store knowledge in linguistic and visual form. For concepts that are hard to explain in writing, creating non-linguistic representations with clay animations can help students explore and remember information. Because science topics range from very small things like atomic particles to very large structures like the solar system, it is difficult to explore many concepts in a tangible way. Clay animation allows for hands-on manipulation and the creation of physical models, helping students analyze scientific structures and processes like cell division and plate tectonics.

Improve Thinking Skills

While students are motivated by creating their final animation products, it is the process of making clay animation, including writing, brainstorming, planning, sequencing, team work, and management, where the real learning takes place. As they plan their clay animation to demonstrate a science process, such as plant growth, students must use logical thinking skills to sequence the steps. Critical thinking skills are required to analyze the process and determine what factors are necessary for each step in the process and movement from one step to the next. As students create the clay animation, they must evaluate the information and work together to determine the most effective way to demonstrate the concept or process they are animating.

Collaboration is a necessary component of successful classroom clay animation. Consider, for example a project on cell division. If each team attempts to animate the entire process of cell division, due to time constraints, the resulting animations might not include all of the essential information and details. On the other hand, if each team were to animate one phase in the process, the entire class could combine their animations into one presentation. The whole class will still need to look at the entire process to determine what colors and shapes to use. This ensures that models display cell structures like the nucleus and cell walls consistently throughout the animation. Each team would also have to work with the team before it and after it to ensure that no part of the cell division process was missed.

Students at Bauer Elementary in Hudsonville, Michigan create a clay animation as the culminating assessment of a unit on plant and animal life cycles. The students choose which life cycle they want to work on, and form groups to make clay animations to demonstrate their understanding. Teacher Julie Myrmel shares, “Not only do they delve deeper into the progression of the life cycles, they get to showcase their artistic side, learn how to compromise as a member of a group, and work on a project they really care about. The element of fun, and the strong sense of ownership of the project, brings out the best in them.”

Engaging ALL Learners

Engaging the intelligences of all students in a classroom is part of what makes clay animation so motivating. Students have seen clay animations on television, and even though they are using animations to represent concepts in science, this makes the project more relevant to their lives. Creating an animation that will be viewed by other students in their class, students in other classes if they are shown at a school assembly, or students around the world if they are shared online, reinforces that the work our students are doing in the classroom is valuable and important.

Julie Myrmel also loves how clay animation engages all of the learners in her classroom:

“One of my favorite parts of working with these projects is that the kids who are often the leaders are the same ones that struggle with more traditional class work. So, instead of being the one who has to HAVE help, they are the experts the other kids go to, and they’re the ones GIVING the help. The look on their faces as they’re sought out as pros by their peers is priceless.”

Anne Truger, of Lake County, Illinois, works with students who have behavioral and learning issues. She can’t reach her students without projects that are motivating. When using clay animation, she found that her students were “more engaged...than I had seen all year. Students gave up study halls, lunch, and even came in early to work on the projects!”

This visual approach to learning also supports the multiple intelligences students use to learn in the classroom. Clay animation provides an opportunity to reach the variety of learners in your class. The parts of a clay animation production help all learners strengthen the different intelligences as they complete their project. Making a clay character engages the bodily-kinesthetic intelligence; writing the story or script engages the linguistic intelligence. Working in a team engages the interpersonal intelligence. Creating an animated production engages the spatial intelligence, and organizing and sequencing the frames and tasks engages the logical-mathematical intelligence.

Assessing for Understanding

The process of creating a clay animation also provides multiple opportunities for assessing understanding. With many traditional forms of assessment, students can recall enough rote information to guess a multiple choice question correctly or parrot back an exact definition without understanding what it means. Creating a clay animation provides many opportunities for you to assess for understanding. Lania Ho, of Barrington, Illinois, asked her students to create clay animations that demonstrated a real-life situation to explain physics concepts they were learning. When students used a martial arts fight to demonstrate Newton’s Third Law of Motion – every action has an equal and opposite reaction - the questioning and planning during the process provided an opportunity to ask questions and identify misconceptions. In this instance, making sure that the students understood that while the action, one character hitting another, was obvious, the reaction was not the other character falling down.

Jean Trusedell, of Decatur, Indiana, used clay animation for a germ unit. Her students created animations that showed how viruses and bacteria attack our cells, how medicine might affect the germ and kill it, and how the cells could be protected. While building the animation, they had to discuss their ideas with their teammates as well as explain their ideas to her. “The greatest part of using clay animation is that the kids are always having to explain the process as they go, and I can constantly assess their progress. Asking them to visualize the cellular level is always difficult; the clay animation process helped make that possible,” she shares.

Making the Investment Worthwhile

The process of clay animation involves a significant time investment. Although there are ways to simplify projects and the process, you would not want to use clay animation to teach every topic in your science curriculum. You can ensure that the time investment is worthwhile by choosing your topics carefully and structuring the process to meet your classroom needs. Using clay animation to explore a difficult topic helps provide multiple opportunities to catch misconceptions, while providing students many opportunities to analyze content. If student teams create animations on many different topics at the end of the unit, sharing the finished animations is a great way to revisit concepts at the end of a unit and review for an upcoming assessment.

Remember, the learning during a clay animation project occurs during the process. Sandra Smits, of Hudsonville, Michigan, explains, “When they were done with the project, they really had a strong understanding of the life cycle because they spent so much time planning it out and talking about the steps involved to make it all work.” The visual format and popular medium appeal to students who might not otherwise engage in the content or be willing to struggle through difficult concepts. Clay animation projects require students to think, not simply recall facts and information. Jean Trusedell sums this up nicely: “Clay animation requires my students to delve deeper into their higher level thinking skills. Rather than learning that is rote, clay animation requires my students to synthesize the facts and turn that knowledge into a new understanding and THEN demonstrate their new understandings to others.”

References

Marzano, R.J., Pickering, D.J. & Pollock, J.E. (2001). Classroom Instruction that Works: Research-based Strategies for Increasing Student Achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

National Committee on Science Education Standards and Assessment, National Research Council. (1995) National Science Education Standards. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.