Use Mind Maps to Improve Learning

How mind maps help students engage more deeply with content, ideas, and the writing process

Mind maps are a powerful tool for helping students make sense of complex content. When students create mind maps, they’re not just copying facts; they’re actively organizing ideas, making connections, and engaging with material in a deeper, more meaningful way.

Student-created mind maps offer teachers a powerful window into student thinking. As students build mind maps, teachers see how they connect concepts, identify key ideas, and structure their understanding. This makes it easier to see where students are excelling or identify misconceptions and adjust instruction.

Here are four reasons to use mind mapping with elementary students.

1. Deepen content learning

When students are explicitly taught how to read and construct mind maps, they show significant improvements in summarizing and remembering information (Merchie & Van Keer, 2016; Merchie, Heirweg, & Van Keer, 2022). Mind mapping supports comprehension and boosts retention by helping learners see how concepts relate rather than treating them as isolated bits of information. Mind maps embody a multimodal approach to constructing understanding that leads to deeper learning and stronger recall (Paivio, 1990).

By organizing information visually, mind maps strengthen comprehension, improve memory, and encourage deeper thinking. As students begin to see how ideas connect, learning becomes more meaningful and more memorable.

Mind maps benefit content learning in all subject areas. For example:

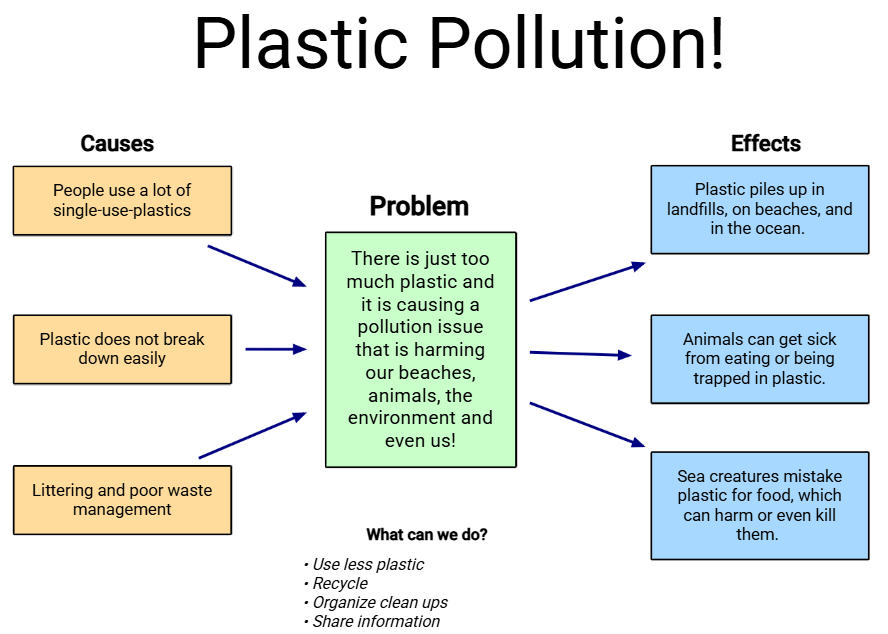

- Visualizing cause and effect in science

Instead of memorizing isolated facts, students analyze relationships and see the interconnectedness of processes, reinforcing recall through visual pathways. - Breaking down complex historical events

Giving structure to historical events helps students to grasp the big picture, understanding how causes led to effects, rather than seeing history as a set of random dates. - Analyzing story structure in language arts

Seeing relationships between characters, plot points, and themes helps students internalize story structure, improving comprehension and retention. - Organizing math problem-solving strategies

Breaking problems into manageable parts encourages logical reasoning and visualizing different approaches to the same problem reinforces flexible thinking.

2. Encourage higher-order thinking and problem-solving

Mind mapping naturally supports higher-order thinking. When students create mind maps, they aren't just recalling facts, they're analyzing, comparing, organizing, and problem-solving. A study by Nesbit and Adesope (2006) found that concept mapping significantly boosts deep learning and problem-solving skills when compared to more passive learning strategies.

Mind mapping is a powerful tool for the thinking and problem-solving required in a project-based learning approach. Mind mapping gives students a space to explore causes, consequences, and possible solutions—turning abstract problems into opportunities for creative thinking and meaningful conversation.

3. Support ideation and organization throughout the writing process

Mind maps are powerful writing tools that help students brainstorm, plan, and organize their thoughts in a way that feels manageable. By seeing their ideas laid out clearly, students can generate multiple possibilities, rearrange them easily, and avoid getting stuck before they even begin.

Mind mapping during the writing process helps students find connections between ideas, plan the structure of their essays or stories, and ensure they cover all necessary details without unnecessary repetition. The upfront planning and organization done with mind maps acts like a writing road map, leading to more coherent, focused, and engaging writing.

Mind maps support stronger structure and coherence, helping students more easily identify key facts for informational writing, lay out arguments and counterarguments for persuasive pieces, or organize main points in a logical sequence for narrative or expository texts.

4. Boost engagement and motivation

One of the most immediate and noticeable benefits of using mind maps in the classroom is how engaged students become. Mind mapping turns learning into an active process, one where students feel like creators rather than just consumers of information. As Felder and Silverman (1988) emphasized, offering multiple pathways boosts confidence, helping helps all students feel seen, capable, and successful.

Tony Buzan’s work (2010) suggests that colorful, flexible formats stimulate the brain in ways that traditional linear note-taking does not. When students are excited to dive into a task, and proud of what they’ve made, they’re more likely to retain the content and more eager to share their thinking with peers (Schunk, Pintrich, & Meece, 2014).

References

Al-Jarf, R. (2009). Enhancing EFL college students’ writing skills with a mind mapping software. CALL-EJ Online, 10(2), 1–13. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED633878.pdf

Anastasiou, D., Wirngo, C. N., & Bagos, P. (2024). The effectiveness of concept maps on students’ achievement in science: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 36, Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09877-y

Boerma, I., van der Wilt, F., Bouwer, R., van der Schoot, M., & van der Veen, C. (2022). Mind mapping during interactive book reading in early childhood classrooms: Does it support young children’s language competence? Early Education and Development, 33(6), 1077–1093. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2021.1929686

Merchie, E., & Van Keer, H. (2016). Stimulating graphical summarization in late elementary education: The relationship between two instructional mind-map approaches and student characteristics. The Elementary School Journal, 116(3), 487–522. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/684939

Merchie, E., Heirweg, S., & Van Keer, H. (2022). Mind maps: Processed as intuitively as thought? Investigating late elementary students’ visual behavior patterns when reading mind maps. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 822949. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9029389/

Mustika, M., Yeh, C. Y. C., Cheng, H. N. H., Liao, C. Y., & Chan, T.-W. (2025). The effect of mind map as a prewriting activity in third grade elementary students’ descriptive narrative creative writing with a writing e-portfolio. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 41(2). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcal.70006

Nesbit, J. C., & Adesope, O. O. (2006). Learning with concept and knowledge maps: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 76(3), 413–448. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3102/00346543076003413

Novak, J. D., & Cañas, A. J. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them. Institute for Human and Machine Cognition. Retrieved from https://cmap.ihmc.us/docs/theory-of-concept-maps

Paivio, A. (1990). Mental representations: A dual coding approach. Oxford University Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-13324-007

Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2014). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed.). Pearson Higher Ed.