Implementing PBL with Make It Matter

Small steps for big advances toward PBL & student-directed learning

Implementing project-based learning (PBL) is more involved than simply adding a student-created deliverable to existing curriculum. While adding a creative component is more engaging and student-centered than a lecture or worksheet alone, it doesn't meet the requirements of an instructional shift to the project-based approach to learning.

In a true project-based learning environment, students don't learn something and then complete a task to show they understood. Instead, they are presented with a problem and must learn content, think critically, and practice a range of skills to solve it. The learning can sometimes be disorderly — and even downright messy, but it also tends to be powerful and deep.

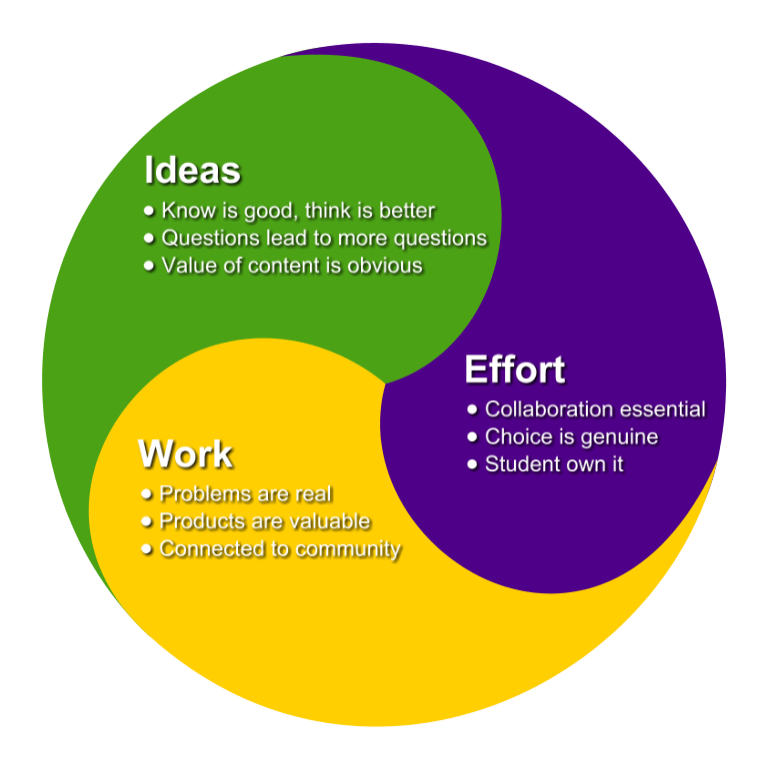

In a recent article, I shared the Make It Matter model for PBL implementation. This model uses three guidelines to help educators evaluate their progress toward PBL: ideas that matter, effort that matters, and work that matters. You can use this model to help you move from doing projects to a project-based approach to learning.

Ideas that matter

Balancing the need to “cover” standards with the goals of building depth of knowledge and critical thinking skills is difficult — but not impossible. Education is getting better at determining “big ideas…” the ideas that matter. Many educators have completed training in Backward Design methods developed by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe. Many textbooks now include the big ideas for each unit or chapter.

Educators nationwide are learning to use these big ideas to develop essential questions for the content they are exploring with students. Essential questions do not have a single definitive correct answer. Sometimes there are many possible answers; sometimes, there may be no obvious correct answer at all. Often the question itself often provokes disagreement and leads to discovery by requiring students to find and grasp important ideas.

The relevance of the big ideas to the curriculum is usually obvious…discovering how to also make them relevant to our students is often the true challenge. Essential questions are a step in the right direction since we are asking our students to think and contribute to an answer rather than merely choosing what we already know to be the correct answer.

Effort that matters

Providing students with a well-crafted essential question (or powerful question statement) engenders further interest in the topic by leading to many more questions. If we want to truly prepare students to think deeply and solve complex issues, they need to learn how to ask questions. Many educators kick off a PBL exploration by have students come up with their own questions about a topic. Students work around the topic is then guided by the questions they themselves have generated.

In the words of Jennifer Geyer, Principal at Cielo Vista Elementary in Palm Springs, California, “If you are really doing PBL that is student-centered, you can't have administrative expectations for ‘when’ or ‘how many.’ You don't know if students will ask questions that take you there.”

A crucial first step in the shift of questioning from teacher to students is to ensure that students have the necessary skills. Students must understand how to craft deep, open-ended questions. You can use the Question Formulation Technique developed by Luz Santana and Dan Rothstein to help students build questioning skills and begin project work. In this process, students are given a Question Focus Statement. Students think, discuss, and begin asking questions about the statement. For example, the statement “revolutionaries have changed the world” might lead students to ask:

- How have revolutionaries changed the world?

- Which revolutionaries have changed the world?

- Can you change the world without being a revolutionary?

- Are revolutionary changes positive or negative?

Students then identify which of their questions are open and which are closed. For example, they could place a “C” next to the questions that are closed, or have a single or correct answer. They could place an “O” next to the questions which are open, or have many answers or opinions.

Learners then expand their questioning abilities by rewriting closed question as open questions and closed questions as open ones. Students will soon realize that open-ended questions are more engaging and more thought provoking, more open to exploration and debate; they will also come to understand that they need to know the answers to many of the closed questions to properly address the open questions.

Student teams next prioritize their questions, determining which they consider the best or most interesting. Then they plan next steps such as choosing which questions will be the focus for their project and how they will begin developing a response.

Work that Matters

“Give pupils something to do, not something to learn; and the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking; learning naturally results.” John Dewey

A project-based approach to learning connects students' learning to the world beyond the classroom. When student do work that matters, they seek to solve real-life problems and address real-world issues.

A universal project seen in elementary schools everywhere is the animal report. Many reports start as a list of instructions: “Research the endangered species who live here and create a public service announcement to educate others. Your PSA should describe the characteristics of the animal, its habitat, why it is threatened, and what actions viewers can take to help protect it.”

The products of such activities have a tendency to look alike. Since all of the project's instructions except the very last bullet point require little thinking, the students produce formulaic reports that enumerate facts about an animal. When students research information and parrot it back in a deliverable, their thinking is not deep. This is not work that matters.

You can move this project toward PBL by combining students' near-universal love of animals with their burgeoning opinions and idealism. Instead of asking them about the animal, ask them to grapple with the very real problems of civilization colliding with nature. Be sure to avoid telling them precisely how to think or exactly what form their artifacts should take. A much more engaging example might be:

“As you learn more about endangered species who live here and explore the various aspects of this issue, choose the opinion you most agree with and argue from that perspective about what actions should be taken. Work to change people's minds or behavior to reflect your opinion.”

One of my favorite non-PBL language arts projects is to have students create book trailers for books they have been reading to encourage other students to check them out at the library. Students are hooked with an engaging introduction: “The librarian at Lincoln Elementary was seen crying the other day because kids are uninterested in checking out library books. The Principal has asked you to help!”

A teacher-directed project like this often includes specific attributes, like:

- The trailer should be 30-60 seconds long.

- You need to hook viewer's interest right away.

- Be sure to include information about character, plot, and setting.

While this is a much more engaging project than a book report worksheet and student deliverables may vary since they've been given more leeway, the project is still more artificial than authentic. It asks students to do something defined by the teacher, made artificially important through a fun hook.

To reframe this and make it more authentic, start with a real problem: the fact that only about one-third of students in fourth and eighth grade score at or near proficient levels in reading. Student-created book trailers constitute a genuine attempt to solve the problem by persuading students to read a particular book, but the task is a teacher-directed solution to the problem, not a student-generated one.

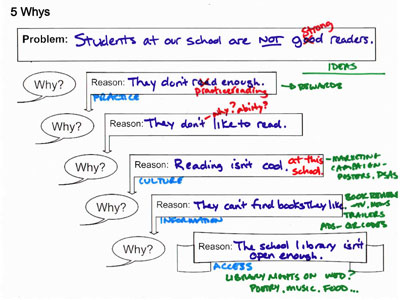

Instead of presenting the solution to the problem as a task for students to complete, ask students to participate in deeper discussions about the problem. Why does it matter whether students are proficient readers? How does literacy affect future earnings and income? Work to ask questions like these, performing the preliminary research as a group. A “Five Whys” organizer can help students determine factors that contribute to such a problem.

The Five Whys methodology was originally developed by Sakichi Toyoda for Toyota to help engineering teams determine root causes of problems. The Five Whys helps identify cause and effect. Students can use the same methods during a PBL activity to identify causes for the problem they have identified and determine possible approaches to solve it.

Rather than reading a list of their teacher's expectations for a specific product, student teams brainstorm questions, ideas, and potential solutions. As they choose from a list of their own ideas, they take ownership of the direction for their work. The result is a range of approaches to solving the problem in your classroom. Some students may end up choosing to create an engaging book trailer styled as a movie preview; others will come up with their own ideas:

- New, more interesting book jackets for titles already in the school library.

- Book reviews aimed at a specific grade level or interest.

- An ALA-style “READ!” marketing campaign.

- Starting a book club at their school.

- A research paper about the connections between education, literacy, and income.

- A handbook for parents to encourage reading at home.

As students gravitate towards their favored approaches, they organically form collaborative teams with common interests and goals. Students' choice of a solution or product is very often (but not always!) appropriate for the abilities of their team members.

Gary Stager reminds us, “Schools have a sacred obligation to introduce children to things they don't yet know they love.” As students are given more control of the process of ideation, teachers transition into the role of coach and mentor, supporting and pushing teams to do their best work.”

While a PBL approach isn't easy, working incrementally toward PBL will move the learning that takes place in your classroom closer and closer to being student-centered and student-driven.