Foundations for Independent Thinking

Breathe new life into the curriculum by changing the end product that students produce

Today’s classroom looks very different from classrooms of even fifteen years ago. Students entering the classroom today range from those with hundreds of hours of computer and Internet experience to those who have little or no access to technology. Some of our students read, write, and speak English fluently; others are second-language learners who primarily speak another language. How can we engage students with such a variety of skills and talents while providing them with important and relevant 21st–century skills like creativity and problem solving?

If we give students a traditional “choose an animal and write a report” assignment, we may have problems challenging or engaging them. Those students with computer experience may head to the Internet, copy and paste information from a couple of sources, print it out as their own, and move on. Our ELL students may not have the reading and writing expertise to really demonstrate their understanding.

Using the principles laid out by Marzano’s Nine Essential Instructional Strategies and Bloom’s Taxonomy as a foundation for structuring our assignments, we can empower all of our students to think creatively and independently. The suggestions and strategies in Bloom and Marzano are rich with verbs such as compare, design, predict, develop, incorporate, and evaluate, making project design easy. When students are given an assignment that encourages higher-level thinking, the opportunity for “data dumping” (copying and pasting) is almost nonexistent.

Back in the 1950s, Benjamin Bloom and colleagues developed a taxonomy that focuses on six levels of thinking. Revised in 2001, Bloom’s taxonomy provides a framework for examining the types of questions we provide our students and the thinking required to answer them. If we give tasks that draw from the four levels of higher-order thinking skills, we run into wonderful verbs like imagine, contrast, and create that help us transform the end product of our assignments to increase engagement, encourage student learning, and avoid data dumping.

In exploring research about effective teaching and learning, Bob Marzano and colleagues identified nine strategies aimed at increasing student achievement by fostering higher-level thinking skills. The first in this list of instructional strategies, identifying similarities and differences, easily lends itself to creative thinking. In this strategy, Marzano stresses the importance of the ability to break a concept into similar and dissimilar characteristics. If students are able to do so, it is likely they will also be able to solve complex problems by breaking them down into simpler parts.

Using Bloom and Marzano strategies does not require us to teach more content, just teach our content a little differently. Let’s look at some ways we can take what we already teach and transform the end result into a creative and unique learning opportunity for students.

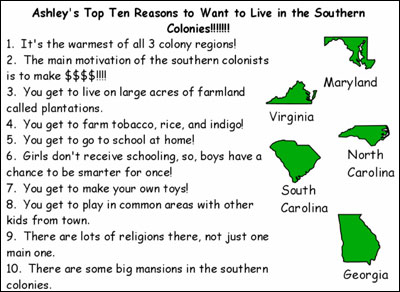

Top–Ten List

Nearly every upper-elementary student is required to do a space report. Most often, the task is to choose a planet and write a report. Many of today’s students will “Google” their planets the night before the assignment is due, copy and paste a few facts, turn in the assignment, and call it a day. As an alternative, task students with creating a top–ten list of reasons why they would or would not like to live on their planets. While they can still go to the Web to complete their research, it is unlikely they will find (or will agree with!) someone else’s top ten reasons not to live on Jupiter.

This opportunity to be creative and thoughtful will help ensure they do not just copy and paste existing data and pushes them to state the facts in their own words and make connections to their own lives. This type of assignment can be used for reporting on places, people, events, animals, and more!

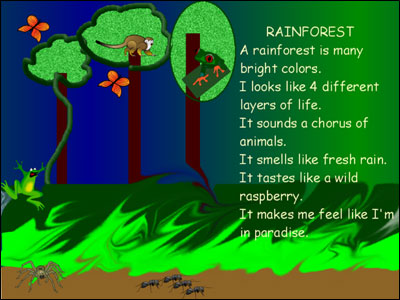

Five Senses

A five senses assignment is great for reporting on places or habitats. Rather than having students write an essay about a habitat, ask them to author a poem about it using their five senses. This requires students to do extensive research to determine what type of landforms, structures, or animals they might see; what types of agriculture they might taste; and so on. Using Pixie, students can support their poems with additional graphics, illustrations, and voice narration, enabling them to synthesize their research into a highly creative end product. Again, this type of assignment makes data dumping nearly impossible.

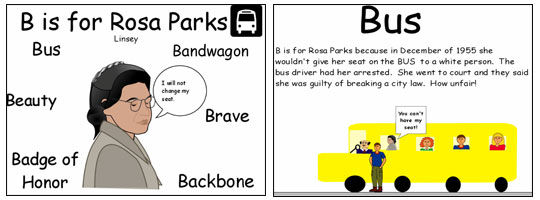

Associative Letter Report

Similar to an ABC-style book, an associative letter report asks students to take what they know about a topic and organize the information around a specific letter. For example, a student assigned the letter “B” and Rosa Parks might write “B is for Rosa Parks because she was brave when she would not budge from her seat.”

This assignment incorporates reference skills by necessitating the use of a thesaurus and encourages problem- solving skills, especially when students have a difficult time finding words to describe their topics. You can even introduce ideas like alliteration to more advanced students to give them additional flexibility with their wordplay.

We use associative letter reports for Black History Month and make sure that each letter of the alphabet is represented. When the project is completed, all of the pages are bound together into a creative and informative book.

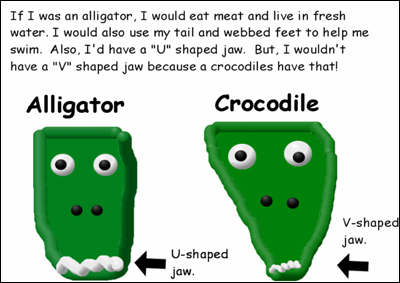

If…But

The “If…But” report is an exercise in comparing and contrasting, which plays a key role in both the Bloom and Marzano frameworks. In this style report, students compare two topics, such as animals, states, or people. For example, if a student is comparing alligators and crocodiles, they might write, “If I was an alligator, I would eat meat and live in fresh water. I would also use my tail and webbed feet to help me swim. Also, I would have a U-shaped jaw. But, I would not have a V-shaped jaw because crocodiles have that.” Since the report is written in first-person, this assignment deters students from simply copying and pasting content.

I often provide specific templates to simplify the process. I ask students to begin with “If I were” or “If I visited” to describe their first topic or place. Then, I ask them to use “But I would not” to describe the second topic. To differentiate for different grades and ability levels, I simply change the number of sentences required.

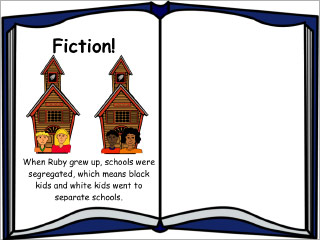

Fact or Fiction

The “Fact or Fiction” report, requiring students to create their own book, is one of my favorite report methods. The front of each sheet of paper includes a “Fact or Fiction” heading, below which the student writes a statement about the topic being studied. On the back of that page, the heading is either “Fact” or “Fiction” depending on whether the statement was true or false. The student also includes an explanation of the answer. When the pages of this report are bound together as a book, the reader sees the first “Fact or Fiction” challenge. When they turn the page, they learn the answer and read the next question.

In Conclusion

Each of these projects, developed using ideas from Bloom and Marzano, provide an opportunity for higher-level thinking and avoid the problem of data dumping. They do not require us to teach new content—we can breathe new life into our curriculum just by changing the end product that students produce once we have taught the content. Students who are afforded a chance to demonstrate comprehension in a creative manner are far more likely to retain information than if they had been required to summarize, match, or recall. As teachers, we have the ability to empower our students to strive for creativity. By stepping outside of the box and providing the right opportunities, we can foster a room full of independent thinkers!

References

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives: Complete edition. New York: Longman.

Bloom, B. S., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals, by a committee of college and university examiners. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: Longman.

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J. E. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Polette, N. (1991). Research without Copying. Marion, GA: Pieces of Learning.